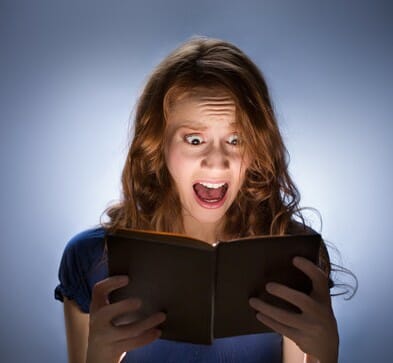

If you’re writing horror, dark fantasy, thrillers or anything else that requires suspense, a good jump-scare or anything that might terrorize your readers, you’ve probably already know that the written word can fill you with dread, and even startle you. Those feelings aren’t reserved for the movies.

But how much study have you put into how your favorite horror authors have gone about scaring you with the written word?

Movies rely on editing, music cues, performance, special visual and makeup effects . . . a whole parade of cinematic tools. But in prose all we have to work with are words, and our readers’ imaginations. The good news is that those are powerful tools.

Though you may not have much control over any individual reader’s imagination, or his interpretation of your work, the ways you arrange words into sentences and sentences into paragraphs can activate your readers’ psyches in ways you may not have thought possible.

It all comes down to breathing

Even when reading silently, we tend to breathe along with what we’re reading as if we were reading it aloud. It’s impossible for us to turn certain parts of our brain off and when something causes us to start breathing differently, that forces us into different states. When you’re in a blind panic you tend to hyperventilate, breathing in quick, shallow gasps. When you’re nervous or anxious about something (the feeling of suspense), you tend to hold your breath, and breathe more slowly.

The good news for horror and thriller authors is that these processes also work in reverse. If you can force that breathing state (or, more accurately, some smaller, less physically traumatic version of that state) in your readers, you’ll bring on the requisite psychological response.

Evoking suspense and anxiety

When you’re building suspense, evoking a feeling of impending doom or the terrifying fear of the unknown, get your reader to hold her breath. Stop her from taking her next breath for longer than normal. And though it may seem impossible to do this with words on a page, remember what I said about how we unconsciously breathe as though we’re reading aloud even when we aren’t.

One of the reasons that sentences are finite is that the period at the end allows us a breath. Paragraphs give us a chance to take a deeper breath. So if you want your reader to slow her breathing and start feeling nervous, anxious or fearful, keep your sentences long, and your paragraphs even longer.

Very near the beginning of Shirley Jackson’s classic The Haunting of Hill House, the protagonist, Eleanor, is on her way to meet her fellow paranormal investigators at a house that’s known to be haunted. Though excited about being a part of something potentially important, and getting away from her dreary life in the city, Eleanor is terrified of what she’ll find there, not just from ghosts but as a result of what we’d now refer to as social anxiety. The closer she gets to the house, the more anxious she is.

Jackson conveys this anxiety with a single paragraph wherein Eleanor makes a stop in a small town along the way and has a cup of coffee. It’s an innocuous scene, but told in a tight POV, it’s incredibly nerve-wracking. This single paragraph consists of ten sentences. The first of those sentences is the shortest at 28 words. The last is the longest at 52 words.

Think about the last time you read, much less wrote, a sentence that’s 52 words long.

By the end of that monster paragraph, Shirley Jackson left her readers gasping for air, and helped solidify The Haunting of Hill House as one of the undisputed classics of the genre.

Eliciting horror and panic

On the flip side, eventually the monster, serial killer or villain finally reveals himself and the terror (a generalized, creepy dread) turns to horror (the visceral reaction to a traumatic event in progress).

Now you want to do just the opposite: Force your readers to breathe too often. Get them hyperventilating. Do this with short sentences. Even shorter paragraphs.

One-sentence paragraphs.

In another classic haunted house tale, Hell House, author Richard Matheson evokes this feeling of panic in one scene of nine paragraphs, each with no more than two short sentences. Readers have been trained to take a full breath after each paragraph, so breaths are coming fast and furious through:

She stopped with a gasp and looked at the Spanish table.

The telephone was ringing.

It can’t, she thought. It hasn’t worked in more than thirty years.

She wouldn’t answer it. She knew who it was.

It kept on ringing, the shrill sounds stabbing at her eardrums, at her brain.

She mustn’t answer it. She wouldn’t.

The telephone kept ringing.

“No,” she said.

Ringing. Ringing. Ringing. Ringing.

I know — technically, that last paragraph has four sentences, but let’s consider that staccato stacking of “Ringing”s as one sentence with partial breaths between each word.

Instead of a single ten-sentence-long paragraph, we have paragraphs of one or two sentences, with the longest sentence/paragraph clocking in at 14 words, or precisely half the length of Shirley Jackson’s shortest sentence.

Following this scene, there are a couple of slightly longer paragraphs as the protagonist tries to take charge of the situation, but this is quickly dismissed by more staccato attacks on the senses. And, like The Haunting of Hill House, the ongoing success of Hell House is proof of its effectiveness.

Putting this technique into practice

This idea of controlling your readers’ breathing is not the be-all-end-all of “writing scary,” but with some practice it will work for you.

And being aware of when to best use this strategy will also prevent you from overusing it, and move the majority of your prose somewhere into the readable, accessible, and comfortable center — until you want things to start getting scary again.

Do you “write scary”? Have you tried this technique to control your reader’s breathing?